The Geometry of Hubris

Primo 2025

Personal

There is a quiet beauty in the circles of Saudi Arabia’s desert farms. Perfectly symmetrical, geometric in their defiance of the barren landscape, they appear almost otherworldly. From the sky, they resemble life itself—a pulse of human ingenuity beating against the stark canvas of the earth. And yet, their beauty is shadowed by something more ominous…

An Essay

The Geometry of Hubris

1

There is a quiet beauty in the circles of Saudi Arabia’s desert farms. Perfectly symmetrical, geometric in their defiance of the barren landscape, they appear almost otherworldly. From the sky, they resemble life itself—a pulse of human ingenuity beating against the stark canvas of the earth. And yet, their beauty is shadowed by something more ominous. These circles are also symbols of our hubris, of our belief that we can bend nature to our will without consequence. They are as mesmerizing as they are frightening, a testament to both our ability to create and our tendency to consume without restraint.

The mindset that built these farms is one of mastery over nature. It is the same mindset that has driven civilizations for centuries—the belief that the land exists for us to cultivate, that resources are there to be extracted, and that technology will always offer a way forward. In many ways, this way of thinking is the foundation of progress. It has allowed us to feed billions, to build cities where once there was only wilderness, to push the limits of what we thought possible. But it is also a mindset that rarely accounts for the limits of the very systems we depend upon. It assumes an endless supply of what is, in reality, finite.

In Saudi Arabia, this illusion of abundance was sustained by deep wells tapping into fossil aquifers—water deposited thousands of years ago, during a time when the region’s climate was far different from what it is today. It was an inheritance, not a renewable resource. Yet, as with so many other natural inheritances, it was treated as something to be spent rather than conserved. The rise of the desert farms was swift, and so was their decline.

It is estimated that Saudi Arabia’s groundwater reserves shrank by 80% over just a few decades. Once the illusion of unlimited water was shattered, the fields began to disappear, the once-green circles turning back into dust.

This is the great paradox of human progress: our ability to engineer solutions that temporarily shield us from natural constraints, while often failing to recognize that the constraints still exist. We see resources as problems to solve rather than cycles to respect. We imagine that we can outpace depletion with innovation. And in many ways, we have—but at a cost that only becomes apparent when it is too late.

Looking at these fields today, we are left with a stark lesson in impermanence. They remind us that growth, when unmoored from sustainability, is merely an illusion of permanence. They force us to confront a fundamental question: can we redefine progress not as an act of conquering nature, but as learning to exist within its boundaries?

The green circles in the desert are no longer as numerous as they once were—but the land cannot reclaim what was borrowed. What was will not be restored in any near future and today the practice has moved to other contries where land are borrowed and water drained as new circles form.

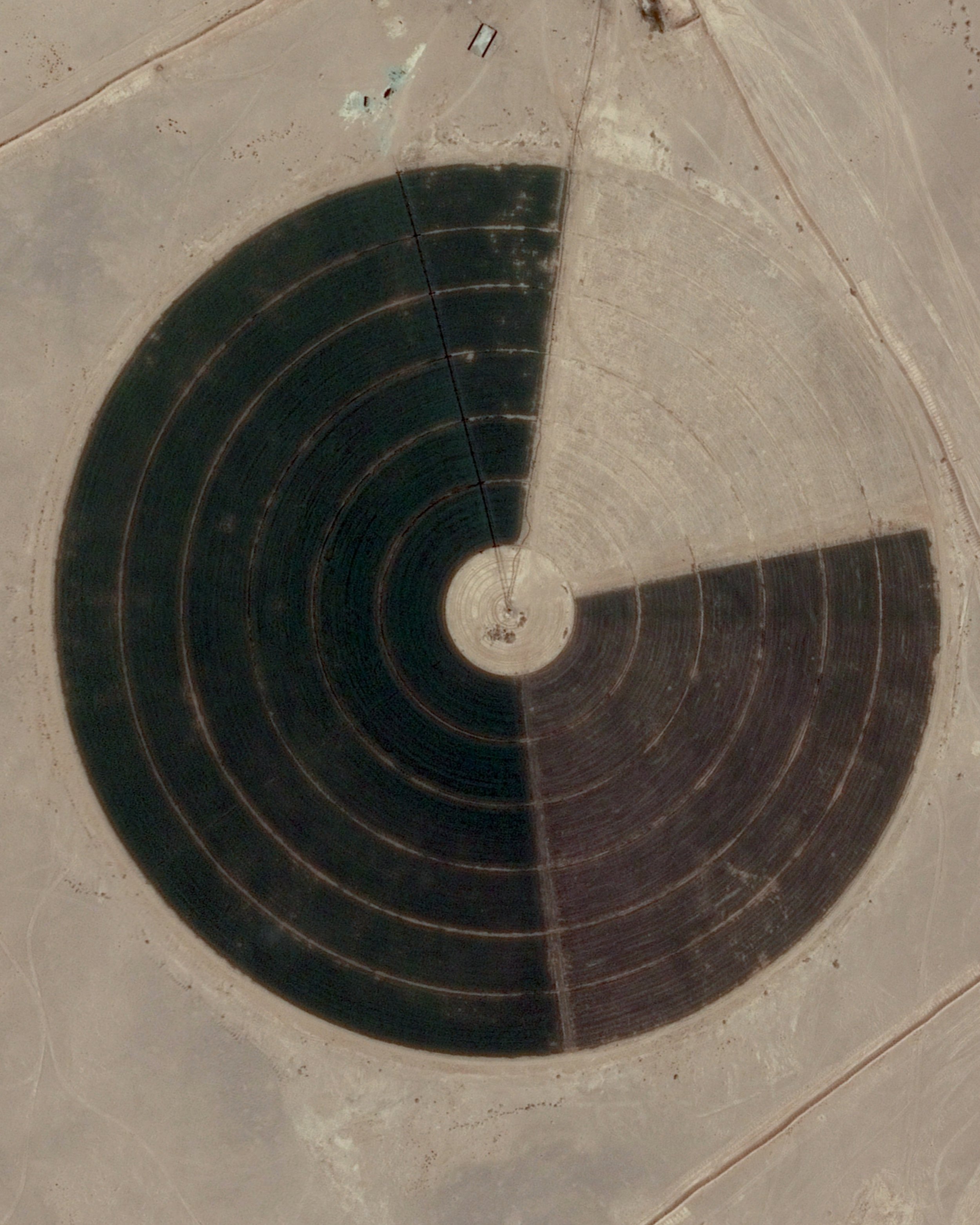

Circle 20

30°10’12.96”N 37°54’42.92”E

02/26/2017

Image © Maxar Technologies

2

what

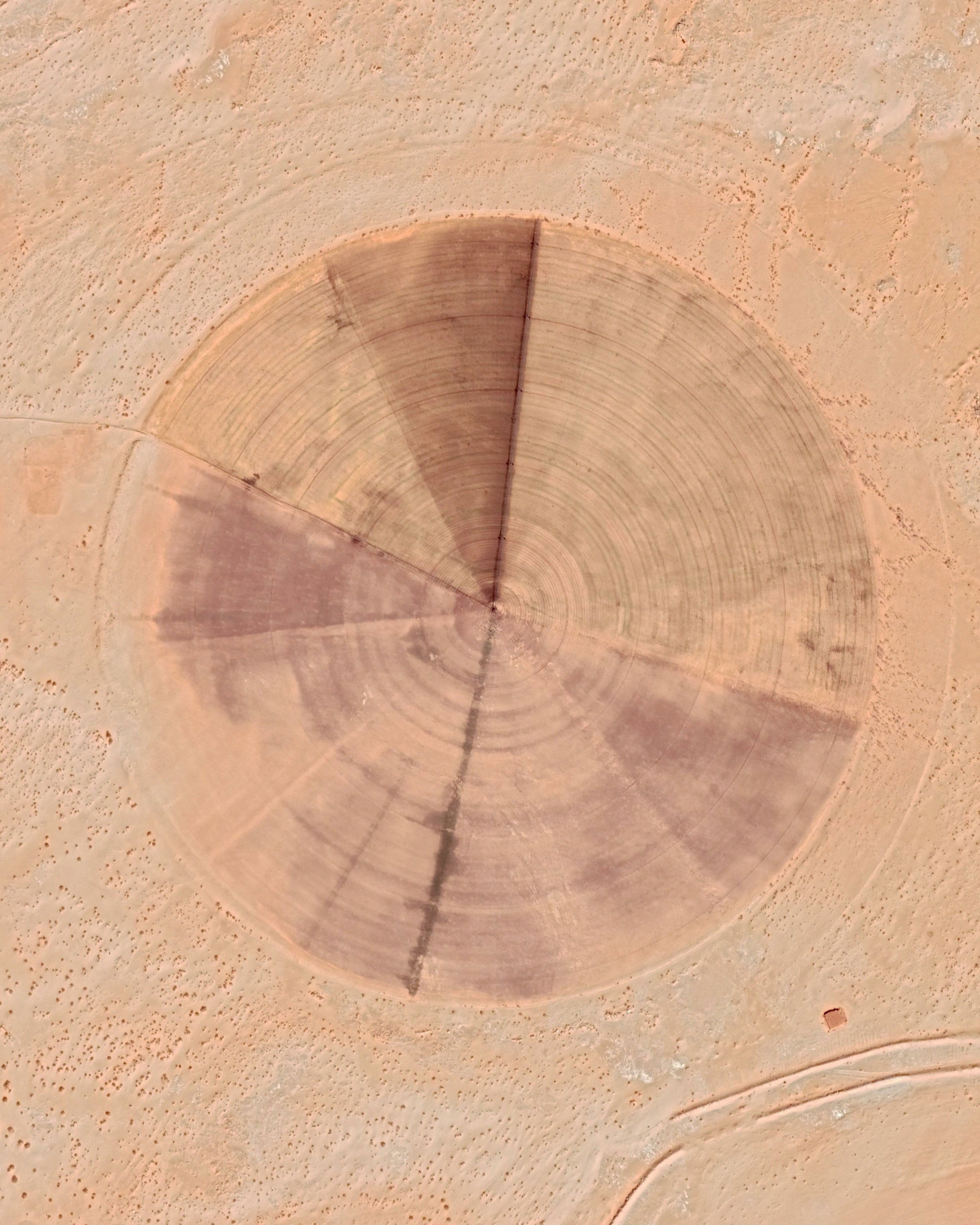

Center-pivot irrigation is an innovative agricultural technique designed to efficiently water crops in large, circular patterns. This system consists of a central pivot point connected to a long, rotating arm equipped with sprinklers. As the arm moves around the pivot, it irrigates the land beneath, creating the characteristic green circles visible from aerial views. Each circle can span up to several kilometers in diameter, optimizing water distribution over extensive areas

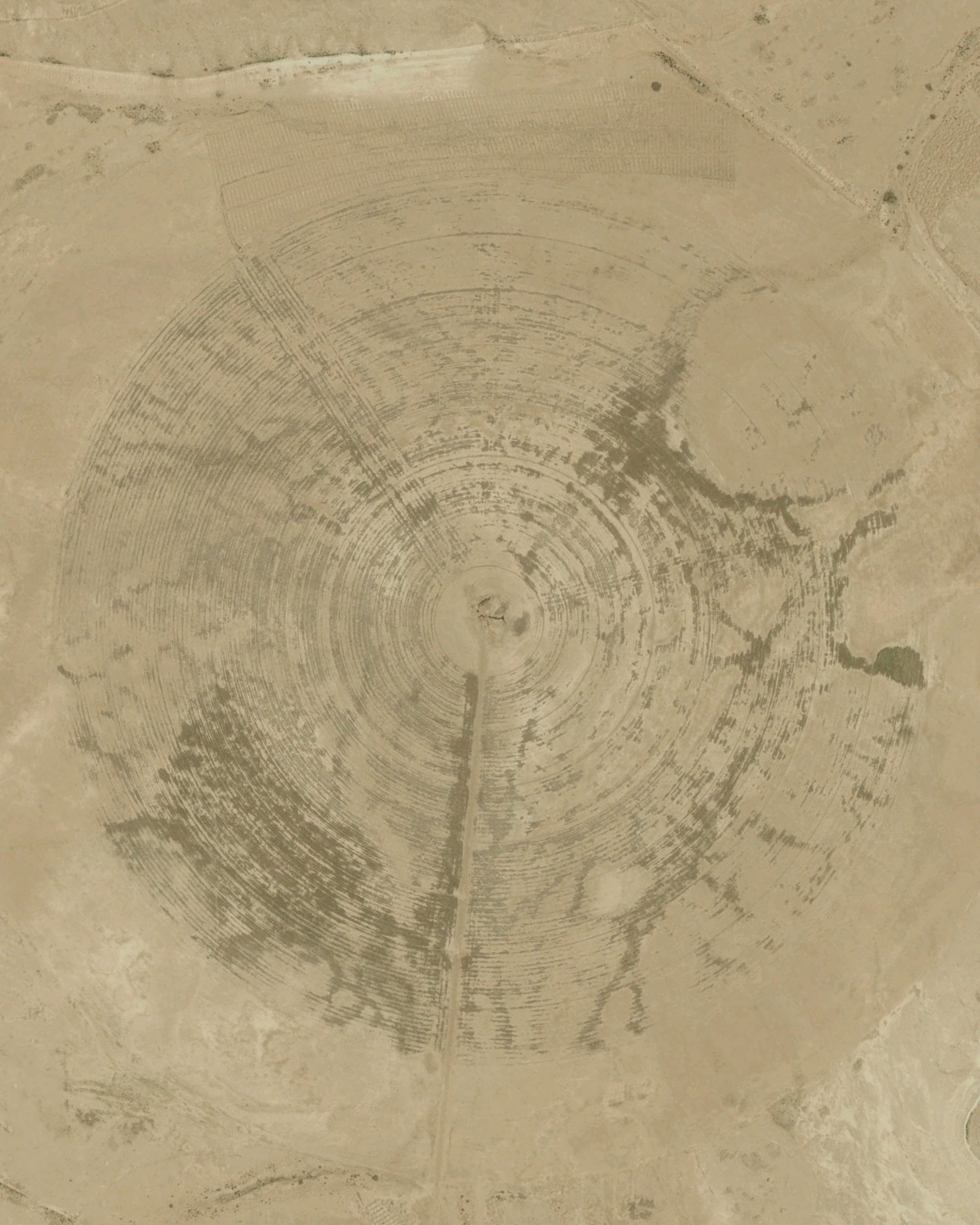

Circle 17

26°30’42.80”N 44°28’45.38”E

10/02/2016

Image © CNES / Airbus

3

why

The driving force behind this agricultural endeavor is Saudi Arabia’s ambition to achieve food security and reduce dependence on imports. Beginning in the 1980s, the nation embarked on an ambitious plan to cultivate its deserts, primarily focusing on wheat production. This initiative was heavily reliant on extracting ancient groundwater reserves, often referred to as “fossil water.” These aquifers, remnants of a wetter climatic period during the last Ice Age, provided the necessary water to sustain large-scale irrigation projects.

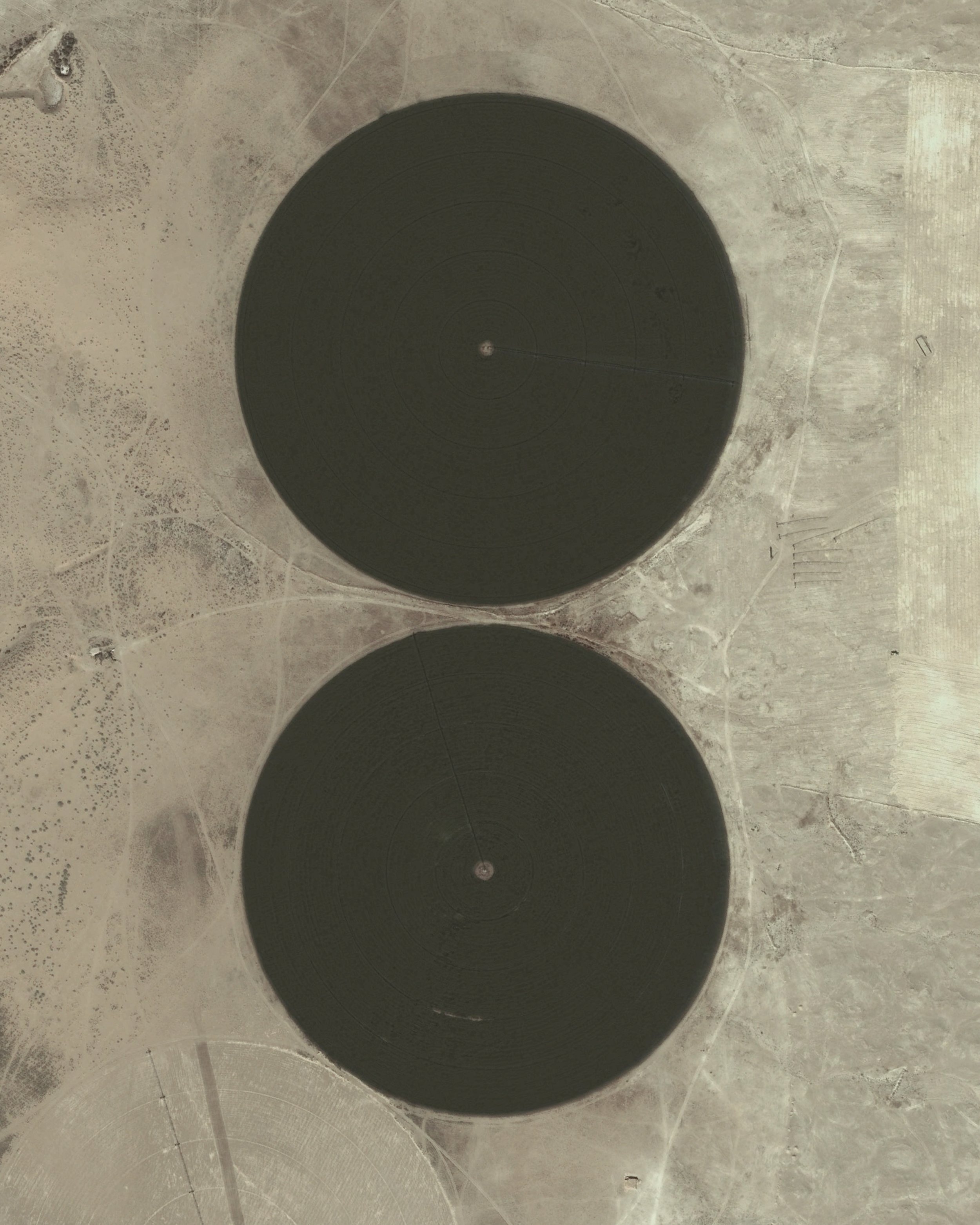

Circle 05

25°01’00.17”N 44°22’27.87”E

08/26/2011

Image © Maxar Technologies

4

impact

While center-pivot irrigation enabled large-scale farming in the desert, it also became an example of unsustainability in its purest form. The system was entirely dependent on finite water resources, drawing from deep fossil aquifers that took thousands of years to accumulate. Estimates suggest that Saudi Arabia’s groundwater reserves were depleted by 80% over the period of widespread agricultural expansion. As a result, the government was forced to scale back wheat production in the 2000s, and many of these once-thriving farms have since disappeared, leaving dry, barren land where green fields once flourished. This highlights the profound environmental cost of large-scale irrigation in arid regions and serves as a cautionary tale about the limits of resource exploitation in the pursuit of agricultural self-sufficiency.