P. Høpner

Oct 29, 2024

Listening to a Place: Understanding Desire Paths

Exploring ‘desire paths’ at the University of Michigan and Toyota’s Kaizen method, this text reveals how understanding natural human behavior can lead to sustainable, human-centered change in organizations.

What Is a "Desire Path"?

The campus of the University of Michigan is a landscape, marked by an intricate network of sidewalks that guide thousands of students each day between classrooms, libraries, and dormitories. These paths, however, are not the product of meticulous planning by architects. Instead, they are the manifestation of something far more organic —the cumulative decisions of countless students who, over the years, have carved out their own routes across the campus. These paths, referred to by architects as “desire paths,” tell a story not just of convenience but of autonomy, rebellion, and the human desire for agency. In this text I examine how architects approaches to human behavior can help organizations onboard employees to change.

When the University of Michigan’s campus was first being developed architects had limited access to concrete and pavement. This scarcity left vast expanses of grass between buildings, and students, driven by necessity and convenience, began walking through these grassy areas to reach their destinations. With each passing semester, these informal routes became more pronounced, as students consistently chose the most direct paths between buildings, regardless of the absence of formal walkways.

These paths reveal a fundamental truth about human nature, encapsulated by Amercan professor and creative writer Andrew Furman: “Desire paths tell us something about the endless human desire to have a choice, the importance of not having someone prescribe your path.” At the University of Michigan and countless other campuses, these paths emerged organically, driven by students’ need to navigate the campus efficiently. Over time, the university acknowledged these organic routes, eventually paving them to accommodate the collective will of the students. What began as mere dirt trails were later solidified into concrete, but not before being shaped by the organic movement.

Another way of observing people’s desires and behaviors in their environments comes from the work of architect Riccardo Marini. Marini has a unique approach to understanding how people interact with urban spaces, one that goes beyond traditional data collection methods. In his work, particularly in collaboration with Danish urban planner Jan Gehl, Marini has paid close attention to the seemingly trivial details of human behavior—details that often reveal much about how people use and move through spaces. One such detail is the location of discarded cigarette butts and chewing gum. Marini observed that these small, often-overlooked pieces of litter could provide valuable insights into where people naturally congregate and linger in urban environments. For example, if he noticed a concentration of cigarette butts or gum in a particular spot on a street, it was a strong indicator that people were already pausing there—perhaps to rest, chat, or simply observe their surroundings. These informal gathering spots, marked by litter, suggested a need for seating or resting places that had not yet been met by the existing urban design.

Informed by these observations, Marini would advocate for placing benches or other seating arrangements in these very locations. The rationale was simple yet powerful: by responding to the evidence of where people were already choosing to stop and spend time, the urban design could better meet the needs of its users. Rather than forcing people to adapt to a preordained layout, this approach involved adapting the design to fit the natural behaviors of the people using the space.

This method of using the patterns of discarded cigarette butts and chewing gum as a guide for decision-making in urban design reflects Marini’s broader philosophy: good design listens to and respects the organic movements and choices of its users. By paying attention to these subtle clues, planners can create spaces that feel more intuitive, welcoming, and ultimately more successful in serving the public.

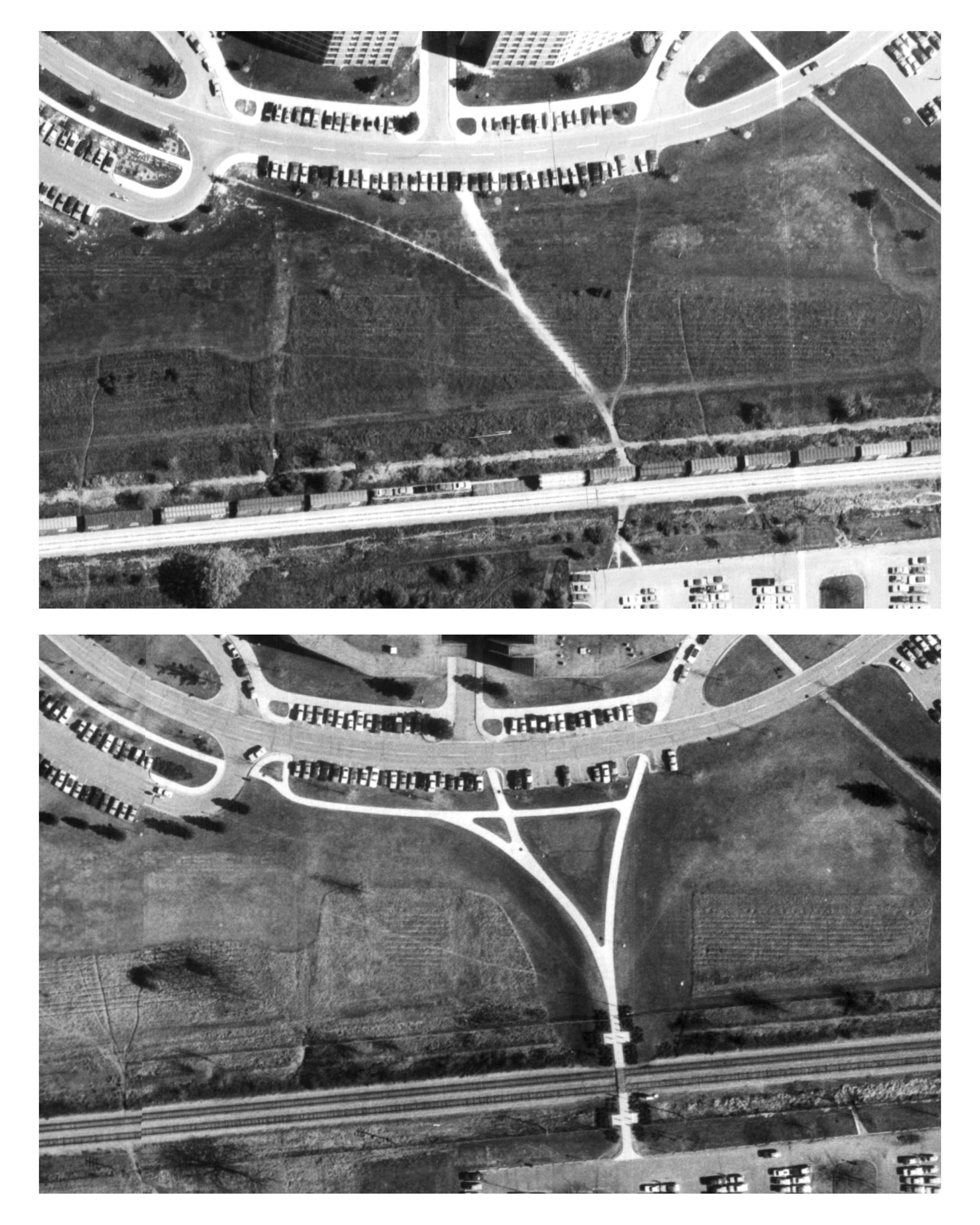

Here'Before and after aerial images (1974 & 1980) of the University of Michigan reveal how landscape architects allowed paths to form naturally in the grass before paving and formalizing the sidewalks on campus.

Desire Paths Embedded Into Work

The desire paths at University of Michigan, represent the spontaneous routes chosen by students who naturally gravitate toward the most direct and convenient paths, rather than those imposed by formal planning. These organically formed paths, later acknowledged and paved by the university, underscore the importance of acknowledging and respecting human desire and autonomy in shaping environments.

This phenomenon parallels the Desire stage in the ADKAR model, one of the most renowned models for managing change in organizations, where individual motivation and personal choice are critical to successful change. The ADKAR model is structured along a timeline that reflects the personal journey individuals go through during a change process in five steps: Awareness, Desire, Knowledge, Ability, and Reinforcement.

Just as students on a university campus instinctively carve out their own paths based on convenience and necessity, individuals in an organization are driven by their own motivations, needs, and desires when it comes to embracing change. The formation of desire paths is an expression of agency, highlighting a natural inclination to choose paths that align with personal preferences, rather than blindly following prescribed routes.

In change communication, acknowledging desire paths on an intellectual level within an organization means recognizing that employees will naturally gravitate toward changes that resonate with their personal and professional needs. The challenge for change managers is to identify and understand these underlying desires and motivations. This can be achieved by addressing a fundamental, yet often overlooked, question that people subject to change often have: What’s in it for me? Even though there might be a strategic and profit-driven decision behind change, this is often far removed from employees’ reality and the daily operations of a company. By answering this question, we can craft change strategies that not only align with organizational goals but also with the natural inclinations of the people involved.

It is well known in change management theory that people are a crucial element of change. As noted in The Missing Link in Change Programmes by Implement (2022), “the recipients of the change are always the most influential change drivers, as they are, in most instances, those who must change.” Yet, much of the prevailing literature treats change as something to be managed, as if we could simply mold people and their behaviors to fit new processes, bending them to our will.

But if there’s a lesson to be drawn from the subtle wisdom of desire paths it’s that people are not easily molded. They have deeply ingrained habits, a natural inclination to seek autonomy, and a resistance to following any path that feels too prescribed. Desire paths remind us that people will often find their own way, one that feels right to them, even if it’s not the most logical or efficient in the eyes of the person planning change.

Kaizen: Integrating Change Within Established Processes and Natural Preferences

With this in mind, perhaps our approach to change should shift. Instead of forcing people onto a predetermined path, we might do better to understand the paths they’re already inclined to take, the ways they naturally navigate their work. What if, rather than imposing change from the top down, we designed it to align with the processes that people already trust and prefer—processes they, in a sense, already desire? Such an approach would not only conserve resources but also tap into the internal motivation that drives genuine, lasting change. After all, the most sustainable transformations are those that people willingly choose to make, rather than those they are compelled to follow.

In the real world, this philosophy finds a powerful example in Toyota’s Kaizen methodology, which demonstrates how embedding change within the natural flow of work can lead to more sustainable and meaningful transformations. Kaizen, which means “continuous improvement,” is more than just a method—it’s a way of thinking that has become an invaluable part of Toyota’s culture. The brilliance of Kaizen lies in its simplicity: it doesn’t ask employees to change how they work, but rather to refine what they are already doing.

At its core, Kaizen is built on the belief that every employee, from the factory floor to the executive suite, holds valuable insights into how their work can be improved. This approach is profoundly human-centric, recognizing that those who perform the work daily are best positioned to suggest and implement meaningful changes. Toyota doesn’t impose top-down mandates but instead invites employees to take ownership of their processes, fostering a culture where improvement is a collective responsibility.

What makes Kaizen particularly powerful is how it taps into a natural human inclination—the desire to make work easier, more efficient, and more fulfilling. Rather than disrupting existing workflows with entirely new systems, Toyota encourages employees to build on what they already know and do well. This approach respects the expertise and intuition that employees bring to their roles, allowing change to grow organically.

The process of Kaizen is both structured and flexible. Employees are encouraged to identify small, actionable improvements that can be quickly implemented. These suggestions are often discussed in small teams, where ideas are refined and put into practice. The quick implementation of these changes creates a feedback loop that reinforces the value of employee input and solidifies a culture of continuous improvement. And like the sidewalks on Michigan University the processes are only paved and structurally anchored when the workers have walked the walk.

The sense of empowerment that Kaizen fosters is one of its most significant outcomes. When employees see their ideas not only heard but also acted upon, it builds a sense of ownership and engagement. This ownership is key to sustaining long-term change—it transforms the process from something imposed on employees to something they actively shape and drive.

Toyota’s success with Kaizen is evident in its reputation for efficiency and innovation. By aligning change with the natural desires and daily practices of its employees, Toyota has created a self-sustaining cycle of improvement that continually enhances its operations. This approach demonstrates how change can be managed not by force, but by understanding and amplifying the ways people already work, making Kaizen a model for human-centric change in any organization. It is a change approach where management sets the strategic goal, but employees have the freedom to choose their path to achieve it building on their knowledge and what motivates them.

Organizations Should Work More With What They Have

The notion of desire paths invites us to rethink how we approach change within organizations. Just as students at the University of Michigan instinctively traced their own routes across the campus, employees, too, will find the paths that feel most natural and intuitive to them. Toyota’s Kaizen methodology shows us what can happen when we acknowledge and build upon these organic movements—when we let change grow out of the routines people already trust.

But is this approach always possible? Of course not. Some changes demand a more direct intervention, a departure from the well-worn path. Yet, whenever we can, shouldn’t we consider the paths already being formed by people? Shouldn’t we ask ourselves: Where are people already going? What procedures and behaviors are they already following and comfortable with that we can support and refine rather than disrupt? For our change activities to truly manifest and take root, we should look closely at the existing systems and routines that employees are already aligned with. By embedding the changes we seek within these familiar patterns, we can foster transformations that feel natural and sustainable. In those moments, the most enduring changes are not those we impose from the outside but those that naturally evolve—following the desire paths that people have quietly chosen, leading to a change that feels not only necessary but right.